In New York City, any tenured educator and member of the UFT who works for the NYC Department of Education and is accused of misconduct or incompetency (2 or more Ineffective APPR ratings) must choose either to go to a hearing, called a 3020-a arbitration, where their specious charges are heard by an arbitrator appointed by the UFT and the DOE and paid by and chosen by the boss (employer)….or be terminated by the puppets appointed to the NYC school board (Education Law 3020-a(2)(f)). This is the conundrum created by the UFT and the DOE to control the mandatory 3020-a process and manipulate the arbitrators hired to do the hearings. While anyone can still win these arbitrations, you need to know the tricks of the trade that challenge you at every step.

It is time to make the 3020-a more fair to the charged educator. Remove the choice cited above between an unlawful charging procedure or termination, re-instate the mandated procedures in Education Law 3020-a(1) and(2), and allow a tenured individual who is charged with 3020-a Specifications to choose his/her arbitrator, a right that all individuals brought to 3020-a arbitration should have, including accused tenured employee members of the UFT in NYC (Education Law 3020-a(3)

In New York State, the only charged educators who do not have the right to choose the arbitrator for his/her hearing are UFT members served 3020-a charges in NYC. CSA (Council of School Supervisors & Administrators)- Assistant Principals and Principals – members have the right to choose the arbitrator in NYC and throughout NY State. UFT members charged anywhere but in NYC may choose the arbitrator.

Education Law §3020-a Changes (Effective April 1, 2012)

Additionally, only in NYC is there no proper determination of probable cause by the school board before charges are served on a charged educator. The Department and the UFT/NYSUT Group remain steadfast that a charged educator must choose a hearing under their terms, or waive the right to a hearing and be terminated. This must change.

Press releases of NYSUT and the NYC DOE give the usual grand view of 3020-a arbitration in New York State without stating the underlying problems which I detail in my posts. Here is a page from NYSUT.org which basically tells you nothing:

Fact Sheet 15-15: Changes to tenure and the tenured teacher removal process (August 20, 2015):

“NYS is widely recognized for its exemplary teaching force and has earned high marks for its rigorous standards and credentialing requirements — typically ranking among the nation’s top ten. Tenure is just one of the safeguards NYS has put in place to ensure every student has an effective teacher. A teacher must earn tenure after successfully completing a probationary period of effective teaching, oversight and evaluation. A tenured teacher then is entitled to a fair hearing before being dismissed — a basic right to due process.

Tenure also provides teachers freedom to advocate for their students without fear of reprisal. Because tenure exists, teachers in NYS can speak out freely on issues such as over-testing; cuts in academic programs; elimination of art, music, foreign language and other programs; and inappropriate programs and services for students with disabilities.

Without tenure, working under the constant threat of arbitrary firing would have a chilling effect on a teacher’s professional judgment and create an environment that would erode, not enhance, educational quality.”

Yet any educator currently working for the NYCDOE walks into his/her school building knowing that the threat to arbitrary charging and firing exists.

The UFT and DOE have bargained away Education Law 3020-a (3)(iii) in New York City in order to set up two panels of arbitrators who they pick, not the charged UFT member. This puts the arbitrators for each panel under the control or at least influence of the employer, the Department of Education. This, in my opinion, allows an implicit bias against a person accused of something. I believe that with the internet, anyone given a list of arbitrators to choose from can do an investigation into the background of each individual arbitrator listed, and in this way assure themselves of a “neutral” hearing officer. The UFT/NYSUT and the NYC DOE did not want anyone to have this right in order to imbed an implicit bias into the procedure.

Additionally, there is no proven correlation between the procedures altered to fit New York City and positive results in terms of teacher training/improvement. I agree with this:

“Even if plaintiffs could establish some generalized correlation between tenure and educational outcomes, it is not obvious that the solution is to

eliminate tenure or terminate teachers. The solution to the problem is bound up in a complex set of public policies and market factors. Any number of different

solutions or combined solutions is plausible”.

(Derek W. Black, “The Constitutional Challenge To Teacher Tenure”, California Law Review, Inc., Vol. 104, No. 1, February 2016, p. 72).

I have given my opinion on this subject and posted on my blogs:

Teacher Tenure 3020-a Hearing Newswire

The Education Law forbids any bargaining away of Sections (1) and (2).

Sections 1 and 2 describe the procedures used to charge employees, and include the Executive Session and vote on probable cause which the NYC and UFT refuse to do for any employee brought to 3020-a in NYC.

New York State Education Law 3020-a: Subpart 82-3 Procedures for Hearings

- 8 CRR-NY II C 82 82-3 Notes

- s 82-3.1 Application of this Subpart.

- s 82-3.2 Definitions.

- s 82-3.3 Charges.

- s 82-3.4 Request for a hearing.

- s 82-3.5 Appointment of hearing officer in standard and expedited section 3020-a proceedings.

- s 82-3.6 Appointment of hearing officer in expedited section 3020-b proceedings.

- s 82-3.7 Pre-hearing conference.

- s 82-3.8 General hearing procedures.

- s 82-3.9 Special hearing procedures for expedited hearings.

- s 82-3.10 Probable cause hearing for certain suspensions without pay.

- s 82-3.11 Monitoring and enforcement of timelines.

- s 82-3.12 Reimbursable hearing expenses.

The New York City Law Department (Corporation Counsel) claims that Education Law 3020-a protects the rights of charged, tenured educators from being terminated at the whim of a Supervisor. In reality, under the current procedures followed by the NYC Department of Education and the UFT/NYSUT Group, we can and do ask “does it?”

*Yes, if the procedures mandated in Section (2)(a) and (3) are followed without the exceptions carved out for NYC, which in our opinion could be argued include the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment:

” No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

*No, Education Law 3020-a hearing without Section 1, and 2 is not protecting the rights of anyone to a fair hearing. Anyone can be terminated by false claims made by anyone for any nefarious reason. This is the business model of public education that Mayor Mike Bloomberg and others high up in the political ladder in the city government desired in 2002 when Mayoral control was implemented. At the hearing, all accused educators must defend against the case for termination presented by the school board by proving a negative – any inference that you are guilty as charged when the event charged never happened.

The UFT/NYSUT and the DOE want their unlawful process to stay exactly as it is, and I have a pile of cases where they submitted ridiculous arguments for the arbitrator to rely on. It is true that the arbitrator will be fired from the panel if he/she agrees with the Motion, so I understand what is going on, but never agree with it. The law should be cited at the pre-hearing to set the stage for an Appeal, if one is needed.

I wrote the Article 75 Petition for Rosalie Cardinale and we won her job back in March, 2018. As I have posted previously on this website, the charging procedure used by the DOE in New York City (and agreed to by the UFT and NYSUT) is unlawful because the NYC school board, the Panel For Educational Policy (“PEP”) is not presented with the charges in order to vote on probable cause, as required by Education Law 3020-a(2)(a):

“2. Disposition of charges. a. Upon receipt of the charges, the clerk or secretary of the school district or employing board shall immediately notify said board thereof. Within five days after receipt of charges, the employing board, in executive session, shall determine, by a vote of a majority of all the members of such board, whether probable cause exists to bring a disciplinary proceeding against an employee pursuant to this section. If such determination is affirmative, a written statement specifying (i) the charges in detail, (ii) the maximum penalty which will be imposed by the board if the employee does not request a hearing or that will be sought by the board if the employee is found guilty of the charges after a hearing and (iii) the employee’s rights under this section, shall be immediately forwarded to the accused employee by certified or registered mail, return receipt requested or by personal delivery to the employee.”

(See my blog here)

The Department attorneys argue that this law does not apply to the NYC DOE. This is a lie, stated into the record so that the arbitrator on the case will agree with his/her employer, the DOE, and not allow any Motion To Dismiss the charges for the omission of the vote in an Executive Session. This is the reason why the NYCDOE and UFT/NYSUT do not want any accused tenured employee to pick their arbitrator: prohibit agreement with any Motion citing the rules, laws, and memoranda which cite violations of law embedded in the hearing procedures unlawfully.

But the law itself is good, and stands for the right to be heard. Whether the arbitrator is listening or not is another matter. The only way to win a 3020-a is to defend yourself against the charges in a professional voice with all the evidence to prove what you are saying, and several witnesses to back your story.

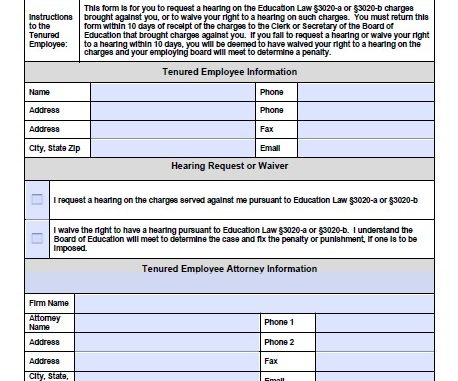

Yet if educators charged with either incompetency or misconduct (two very different panels), do not check off the box saying that they want a 3020-a hearing, and bring this to the UFT for filing within 10 days of being served charges, what happens next is that the Panel For Educational Policy goes into an Executive Session and votes to terminate the educator. So, I always urge anyone who asks me what to do after being charged to check off the box saying you want a hearing. However, no one must agree to have a NYSUT Attorney, you can put “will hire a private Representation” on the form, or switch from NYSUT to a private representative of your choice. In fact, anyone charged can go “pro se” without any representation. At no time should anyone waive the right to a full hearing with a proper defense against the charges unless you are guilty of them and don’t care that you will be permanently on the Problem Code no hire list at the Office of Personnel Investigations.

Here is the form currently used for zoom meetings for the 3020-a: 3020-a zoom request

All the forms sent in the charging packet except for the Specifications against the educator are here:

Teacher Tenure Hearings (3020a)

In my opinion, after doing arbitrations against charges brought against employees by the NYC DOE for 20 years, I believe that the destruction of rights begins way before anyone is put into a 3020-a hearing, but certainly, the fraud continues after testimony begins. Testimony given by the DOE witnesses often has false statements made to push the narrative along that the accused is guilty of the charges and must be terminated. What an accused educator and his/her legal representative(s) should do is unravel the lies and violations of rules from day one of a teacher’s career. There are signposts everywhere. The person assisting/representing the accused educator should know every document and call every witness relevant to the case. I am always most happy when someone asks for my help way before charges are filed because then I have time to solve the mystery of why the charges were created in the first place. I still believe that a proper determination of probable cause (Education Law 3020-a(2)(a)) along with a properly conducted investigation into the charges before a set of these Specifications is created, can change everything and make the teacher trial fair, as it should be.

Unfortunately, NYSUT attorneys do not seem to want to look at the backstory of a particular case, and do whatever is the minimum, to get the case on before an arbitrator and finished as quickly as possible.

See:

The 3020-a Arbitration Newswire: Digging Up The Garbage On the UFT/DOE Partnership of Harm For Charged DOE Employees

The 3020-a arbitration is no place for litigation on Constitutional matters, but is the stepping stone to a lawsuit/petition/Appeal that must be taken after an Opinion of the arbitrator is issued, even if the accused is exonerated. Thus I believe the passing of H.H.R. 4445 may begin an overhaul of the 3020-a charging procedure I have written about for so many years. What should change in the teacher trials is the process of creating the charges, but not the hearing itself. Tenure Law and rights remain public policy in New York City and should remain.

I am posting below H.R. 4445, the new bill passed by the New York State legislature, in order to have this conversation about 3020-a. Ms. Gerstein writes in her post below in HRDIVE:

“Today, forced arbitration is coming to an end for victims of sexual harassment and assault. Our challenge for tomorrow: ensuring that all workers whose rights are violated have meaningful access to justice.”

We need to implement fair arbitration procedures, or a judicial review of charges, without having the accused forced into choosing the mandatory, unlawful version of 3020-a arbitration or termination.

Betsy Combier

betsy.combier@gmail.com

Editor, ADVOCATZ.com

H.R.4445 – Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Act of 2021

Ending forced arbitration of sexual misconduct claims is critical—but not enough

In welcome news last week, Congress passed a bill that would prohibit employers from forcing their employees to go through arbitration—instead of accessing the courts—to settle cases of workplace sexual harassment or sexual assault.“The passage of this bill is a tremendous victory for workers and for justice,” says EPI senior fellow Terri Gerstein in an NBC News op-ed. But, she says, “it’s not the end of the battle.”Workers need to be able to access the courts whenever their rights are violated, says Gerstein, noting that workers are vulnerable to “all kinds of mistreatment, from dangerous working conditions to wage theft to race discrimination.” Read Gerstein’s op-ed

By Terri Gerstein, fellow at the Harvard Labor and Worklife Program and at the Economic Policy Institute

Finally, some good news came from Congress. The Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Act passed in the Senate on Thursday and heads to President Joe Biden to be signed. The bill prevents employers from forcing their workers to bring sexual harassment or assault cases before secretive arbitrators paid by the boss, instead of before judges in open court.

With bipartisan support, its passage provides a welcome example of progress despite our deep divides. It had bipartisan sponsorship from the start: A version of the bill was originally proposed back in 2017 by two of its current sponsors, Sens. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., and Lindsey Graham, R-S.C.

In the years since the bill’s 2017 debut, the country has learned about how widespread workplace sexual harassment and assault are. The sordid phenomenon occurs in places as disparate as seemingly glamorous jobs in Hollywood and the halls of governmental power and in grittier underpaid jobs in fast-paced fast food joints and agricultural picking fields.

But it’s also become even more clear, especially since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, how vulnerable workers are to all kinds of mistreatment, from dangerous working conditions to wage theft to race discrimination. The passage of this bill is a tremendous victory for workers and for justice; at the same time, it’s not the end of the battle. Thursday’s genuine advance should be the first step toward ending forced arbitration for all kinds of workplace disputes.

Since the bill’s initial introduction in 2017, there have been a powerful reckoning and an airing of truths about sexual harassment and assault at work. Harvey Weinstein was convicted. Andrew Cuomo resigned as governor of New York after multiple sexual harassment allegations were made against him that district attorneys described as “credible” and “deeply troubling” but not meeting requirements for criminal prosecution. (Cuomo denies any wrongdoing.)

McDonald’s workers, with help from the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, sued the company alleging a culture of sexual harassment; they also went on strike to protest the company’s approach to these problems. A report by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine found that sexual harassment was widespread in the academic sciences; surveys among restaurant and fast food workers, as well as the general public, have found the same. Major tech companies experienced walkouts and protests. Ultimately some of them ended forced arbitration not just for sexual harassment claims but for all workplace claims. A 2018 New York Times retrospective included 201 powerful men brought down by #MeToo. The list would be even longer by now. Countless women have experienced grotesque violations at work — having their breasts and buttocks grabbed or facing retaliation or termination after refusing the sexual advances of a boss, as Gretchen Carlson alleged.

But these violations aren’t all that’s come to light of late. The disparity of power between workers and employers has led to all kinds of other violations. Wage theft is rampant: A recent Economic Policy Institute report found that $3 billion in stolen wages was recovered for workers from 2017 to 2020 – and this is likely only a fraction of the money actually owed to workers, given workers’ fear of retaliation, the difficulty of finding lawyers and other barriers to filing complaints.

These violations have profound impacts on people’s lives. For example, in one case we handled in my prior job at the New York Attorney General’s office, a home health aide who hadn’t been paid for around two months of work was evicted because she couldn’t pay her rent. Wage theft is also a public health problem: Some experts have noted that the resulting income insecurity makes it hard for people to pay rent or heating bills, buy food or get access to transportation, which can ultimately adversely affect health.

Too many workers also face racial discrimination on the job. High-profile examples abound: In October, a jury ordered Tesla to pay a Black former contractor $137 million based on race discrimination allegations, and just Wednesday, California’s civil rights agency sued Tesla in state court after it said it received hundreds of worker complaints about racial slurs and epithets, discrimination and a hostile work environment. Former Miami Dolphins coach Brian Flores filed a federal lawsuit against the NFL this month, alleging discrimination in hiring practices by teams throughout the league. But there are also countless lower-profile discrimination cases that never hit the headlines.

Are wage theft and race discrimination as bad as sexual harassment and assault? The question makes no sense. Oppression olympics aren’t a helpful exercise, and the bottom line is that these workplace abuses are all pretty reprehensible.

However, a tremendous number of workplace cases of all kinds never come to light, because more than half of U.S. workers are subject to forced arbitration, according to a 2019 Economic Policy Institute report. As a condition of employment, they’re required to give up their rights to bring cases before judges and instead agree to a secretive process before arbitrators paid by their employers. Forced arbitration is terrible for workers; as Sen. Graham stated in 2017, “Mandatory arbitration employment contracts put the employee at a severe disadvantage.” Typically, such workers are required to give up their right to bring class actions, too; if they file before arbitrators, they have to go it alone. The Supreme Court, in dire need of reform itself, has blessed all of this, with tortured interpretations that favor forced arbitration over basic fairness.

Research shows that workers lose more often in forced arbitration and win less money than in court when they do win. And forced arbitration’s secretive nature prevents workers from finding out there are ongoing problems in their workplaces. A worker experiencing sexual harassment, wage theft or race discrimination wouldn’t know about other cases because past arbitrations aren’t public record, unlike court proceedings.

And it’s nearly impossible for such workers to find lawyers; attorneys generally can’t afford to bring one-off arbitration cases because the damages are too small to cover their litigation costs and time. One New York University scholar described the “black hole of mandatory arbitration” and estimated that over 98 percent of the employment claims that otherwise would likely be brought are never filed in arbitration.

But forced arbitration doesn’t just harm companies’ current employees. It also affects job seekers, who lack information about the true nature of their potential employers. It hurts employers that don’t force their workers into arbitration: They may well offer better work environments, but they lose what should be a competitive advantage when rivals hide wrongdoing from view. And forced arbitration’s lack of transparency harms shareholders, who make decisions based on incomplete information about companies’ real potential liability.

I worked in state government for many years; I understand that change is often incremental, and making imperfect progress is sometimes better than being ideologically pure while standing still. Sometimes a partial victory can get a foot in the door. Somehow Republicans grasped the problem with forced arbitration in relation to sexual harassment specifically.

Was it because of the #MeToo awakening? The fact that the most visible advocate on the issue — Gretchen Carlson — was relatable to them? Was it a sense of chivalry about protecting wives, sisters and daughters? For whatever reason, it allowed for real progress. And now we have something genuine to celebrate that will make a difference in thousands of working people’s lives.

At the same time, it’s just a first step. Today, forced arbitration is coming to an end for victims of sexual harassment and assault. Our challenge for tomorrow: ensuring that all workers whose rights are violated have meaningful access to justice.

After the #MeToo bill, is the future of mandatory arbitration in question?

Congress recently passed a law banning mandatory arbitration in cases of sexual assault and sexual harassment, rendering the future of the controversial practice unclear.

Published Feb. 22, 2022

Emilie Shumway Editor, HR DIVE

The U.S. Senate, by voice vote alone, voted Feb. 10 to pass the Ending Forced Arbitration for Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Act, also called the #MeToo bill. Earlier that week, a version of the bill passed the House in a similarly sweeping 335-97 vote. The swift, bipartisan movement through Congress was a strong action of censure for one use of a corporate practice that many learned about in the wake of #MeToo: forced or mandatory arbitration.

As its name suggests, the recently passed bill — which President Joe Biden is expected to sign any day — only applies to claims of sexual assault and sexual harassment. It invalidates arbitration agreements that prevent the claimant from filing a lawsuit and seeking redress in court.

While the bill’s text may be straightforward and concise, its passage has garnered major, mostly positive attention politically and in the media. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., one of the bill’s co-sponsors, called it “one of the most significant workplace reforms in American history.” Time Magazine referred to it as a “#MeToo milestone.”

With such significant support for ending one aspect of mandatory arbitration, are other uses for the process next on the chopping block?

A brief history of mandatory arbitration

Before exploring where it stands now, it’s worth noting how mandatory arbitration became so commonplace for employers. The practice emerged from the Federal Arbitration Act, legislation from 1925 that allows for private dispute resolution outside the judicial system through arbitration. Often, this practice is used between businesses as a cheaper and faster alternative to court-provided resolutions.

In 1991, the U.S. Supreme Court issued Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., a landmark decision upholding the enforceability of an arbitration clause between an employer and an employee with age discrimination claims. This paved the way for employers to require employees to sign arbitration agreements — or employment contracts with mandatory arbitration clauses — to avoid use of the legal system.

This decision was a game changer for employers. Due to the privacy of arbitration, data can be hard to come by. According to an estimate from the Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank, however, the share of workers subject to mandatory arbitration rose from just over 2% in 1992 to roughly one-quarter of the workforce by the early 2000s. Per the same analysis, the share of workers subject to mandatory arbitration now exceeds 55%.

In 2018, the Supreme Court ruled on Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, finding that arbitration agreements that require individual arbitration are enforceable under the Federal Arbitration Act. The decision allows employers to restrict workers from filing class action lawsuits and instead require that they pursue claims individually through arbitration.

How it works

Employees (or former employees) who decide to use arbitration typically will approach company leadership or an HR representative, who will direct them to file a claim. Two arbitration organizations dominate in the employment arbitration space: the American Arbitration Association and JAMS Mediation, Arbitration and ADR Services.

If an employee first attempts to sue — many workers do not initially realize they signed mandatory arbitration agreements — the company will usually respond with a motion to stay the case due to the arbitration clause. The court will then either stay the case until the arbitrator reaches a decision or dismiss the case outright, Aaron Goldstein, partner at Dorsey & Whitney, told HR Dive.

The process that unfolds after that tends to look like a slightly less formal version of a legal proceeding, minus the jury. Usually there is a single arbitrator, but in more complex cases, there may be a panel. The claimant and employer each file statements.

“The next step is usually to have some amount of discovery, like you would [have] in a court,” Goldstein said, such as gathering depositions from witnesses and requesting and gathering documents. “Frequently, that process will be a little more streamlined [than in court], and the arbitrator will work with the parties to come up with an appropriate discovery plan for the particular case.”

The discovery process works toward an arbitration hearing, which involves one to two days of argument and testimony. Then the arbitrator hands down a decision.

While the arbitration process tends to take less time than the judicial route, it can still be lengthy. “I think getting something resolved within a year is pretty typical,” Goldstein said. “Often, you shoot for shorter. It’s just that reality often encroaches [with] scheduling people’s depositions … people get busy.”

Finally, the arbitrator issues a decision — typically, if the arbitrator finds in the employee’s favor, a cash settlement of some kind.

The backlash

Arbitration can have many benefits for the employer — privacy and cost effectiveness being perhaps the most notable. But the process has also drawn scrutiny and criticism from worker advocacy groups and other political organizations, and not only in cases of sexual harassment and sexual assault.

The power differential is one factor in worker advocates’ complaints. When two businesses come together and form an arbitration agreement, they tend to be equals, or equally free to enter into the agreement. There is more likely to be an element of negotiation.

But workers have historically been more dependent on a job offer than the employer is dependent on them. “Who would risk a valuable job opportunity … over an obscure procedural provision?” EPI questioned in a briefing paper on the topic. As “mandatory” arbitration implies, a worker likely loses out on an offer if they refuse to sign such an agreement, or at least must weigh the risk of doing so.

Opponents of the practice also argue that arbitrators are incentivized to find in employers’ favor, due to employers holding the contracts and the potential for repeat business. “Research has found that employees are less likely to win arbitration cases and they recover lower damages in mandatory employment arbitration than in the courts,” wrote Alexander J.S. Colvin, author of the EPI report and professor of conflict resolution at Cornell’s Industrial and Labor Relations School.

Arbitration can further be interpreted as a DEI issue: EPI has noted that women and Black workers are more likely to be subject to the practice.

Is there an ‘ideal’ form of arbitration?“There’s what I would call the old, dark playbook: Keep it quiet, pay people off and move on. And then there’s the new playbook, which is the only playbook as far as I’m concerned: Act quickly, act decisively, act publicly. So you don’t have any dirty laundry.”

Aaron Goldstein, Partner at Dorsey & Whitney

One of the more pernicious aspects of many arbitration agreements is the added use of nondisclosure agreements, Goldstein said. Such policies require claimants to maintain silence about their experience as part of their agreement. Goldstein counsels employers not to use nondisclosure agreements, in part because they’re “such a bad PR hit.”

“There’s what I would call the old, dark playbook: Keep it quiet, pay people off and move on,” Goldstein said. “And then there’s the new playbook, which is the only playbook as far as I’m concerned: Act quickly, act decisively, act publicly. So you don’t have any dirty laundry.”

In cases of harassment, retaliation and other law-breaking, for example, employers can protect themselves by following established best practices: investigating claims, disciplining (and sometimes removing) the offending workers and reiterating company policies.

The use of nondisclosure agreements can also result in hefty payouts, particularly if the claimant happens to have more resources and be well represented. Goldstein noted this can occasionally lead to seemingly ironic support of NDAs by claimants’ legal representatives, as it can allow their clients to collect a larger award. While a company may appreciate avoiding a PR catastrophe in the wake of a scandal — and may have deep pockets — NDAs can also be used to protect predators and sustain a toxic culture, which rarely remains in the shadows for long.

Though mandatory arbitration tends to be publicly unpopular and yet still a route many employers take, the story of arbitration itself is more complicated than it may seem. There are reasons employees would choose to use arbitration, and also reasons employers may not want to.

“In the not-so-distant past, I represented plaintiffs myself, and there are some instances where plaintiffs want privacy — the privacy of arbitration,” Christie Del Rey-Cone, partner at Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp, told HR Dive. “There are some instances [in which] they don’t want their story to be publicly accessible for any variety of reasons that make a lot of good sense.”

On the other hand, employers who go the route of arbitration lose out on the opportunity to have the employee’s complaint dismissed on summary judgment — upon judicial review, without a full trial, and often quickly. Summary judgment dismissals are extremely common in employment law cases; one 2013 analysis found summary judgment was granted, in whole or in part, in 77% of employment discrimination cases, for example.

Arbitration cases typically do not use summary judgment because there’s no jury, Goldstein said. Arbitrators figure they “might as well have a hearing.” Going all the way to an arbitration hearing when summary judgment might have been the alternative can sometimes be “as expensive and inefficient as going to court,” Kevin White, partner at Hunton Andrews Kurth, told HR Dive.

Employers that are concerned about fairness, talent retention, DEI and public reputation can choose to dispense with mandatory arbitration altogether, giving employees a choice in how they manage complaints. Google ended the practice in 2019, for example.

Companies hesitant to pull the policy entirely could follow Goldstein’s advice and end the use of nondisclosure agreements.

What comes next?

#MeToo was a once-in-a-lifetime movement, so does it stand to reason that the political and social push to eliminate mandatory arbitration will end with cases of sexual assault and sexual harassment?

It’s hard to say.

Many members of the Democratic party have signaled a broader interest in ending the practice entirely. Last March, Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., introduced the Forced Arbitration Injustice Repeal (FAIR) Act alongside 39 other senators, referring to the mandatory arbitration process as “rigged” against workers. The bill also applies to mandatory arbitration in consumer, antitrust and civil rights cases.

The FAIR Act has not moved since its 2021 introduction, and it has been introduced repeatedly, without much action, since 2017. But enthusiasm for the #MeToo bill may add momentum. In addition, the bill has garnered support from a long list of advocacy groups, including Public Citizen, the National Organization for Women and the Disability Rights Legal Center.

In announcing its support of the #MeToo bill, the White House made clear its own commitment to tackling mandatory arbitration more comprehensively. “The Administration … looks forward to working with the Congress on broader legislation that addresses these issues as well as other forced arbitration matters, including arbitration of claims regarding discrimination on the basis of race, wage theft, and unfair labor practices,” a memo from the president’s executive office stated.

“I think you’re going to continue to see the Biden administration try to broaden the ban on arbitration and employment,” White said. “And I think you’re going to continue to see the states try to enact legislation … I think they will try to get into discrimination generally, and into wage and hour. But I think it’s going to be at the legislative level that the attack is made. Court cases have generally not been very successful. Courts typically uphold mandatory arbitration under the FAA.”

But even without legislative force, corporations may decide to excise the practice on their own. The balance in the labor market has shifted, and employers are looking for ways to appeal to workers. “In this labor market, people are really trying to attract talent,” Goldstein said. “And anything that is a barrier to getting people on board … employers are going to throw out.”

Google’s shift away from the practice followed pressure from employee activists, who staged a walkout of approximately 20,000 employees and formed their own action group. Similar actions from employee activists at other companies could cause the dominos to start to fall more quickly but without major pressure, “I don’t see it going too far too fast,” Del Rey-Cone said.

“These cases can be rather intense emotionally, they can have salacious facts,” she continued. “There’s just all sorts of things that go with an employment claim that makes it very alluring to an employer to know they’re protected from that splash of press, which can be a very big distraction from the actual legal proceedings, [and] can be a big distraction from a business perspective.”

Follow Emilie Shumway on Twitter

Be the first to comment