The abundance of opinions on the JANUS decision just shows what a hot topic this is. The only outcome that anyone can guarantee at this point is that Unions throughout the U.S. will change in some big or small way to earn/win/argue for members.

This is a good thing.

Why do I believe this is a good decision for unions and members?

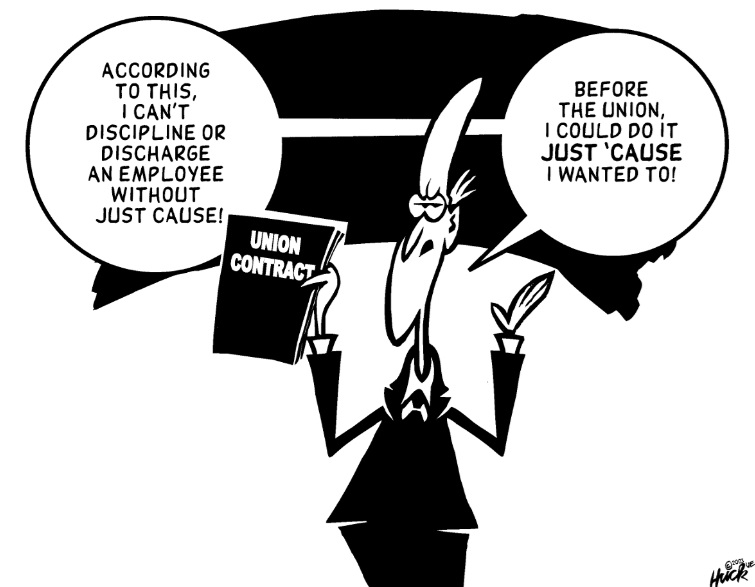

First, change happens everywhere, in all companies, groups, and organizations and in relationships, both personal and interpersonal. When change does not happen for a very long time the ties that bind go stale. I think it was time to take a look at what unions across our vast country were doing for the members, and to examine closely whether or not the actions taken by the union top dogs earned the members’ allegiance and dues money. Sadly, many union Presidents have forgotten the rank and file or allowed their inner circles to abandon the rule that members needed to be represented and their rights honored above all else. Political interests were permitted to become the collective voice before the collective voice of members uttered a word, or after. Dissention was scorned. This is not good.

I remember the 2016 election for United States’ President when the United Federation of Teachers in New York City came out and urged members to vote for Hillary Clinton. OK, that’s fine, if the opinion gives opposing opinions equal time. However the backlash we in NYC saw against any member who did not want to vote for Hillary was not OK. It became ugly, with hate-filled rants by UFT members about anyone who spoke up about disliking Hillary for any reason.

Second, the JANUS decision does not mean the end of unions but the beginning of a more considerate union movement which honors and respects the members, their rights, and their money.

See:

How will the upcoming Janus Supreme Court case impact teachers in each state?

“At the center of the Janus case is whether public sector unions are legally allowed to collect “agency fees” from non-union members. Agency fees, also known as “fare-share” fees, are fees paid by non-union members to the union in order to cover the cost of collective bargaining on their behalf. Because union members and non-members alike stand to benefit from a contract the union negotiates, the theory goes, non-members should have to contribute something to the costs of collective bargaining. Janus challenges this logic, arguing that these fees violate non-members’ First Amendment rights by requiring the monetary support (which counts as speech) of certain political stances taken by the union on teachers’ behalf during collective bargaining, regardless of whether the teacher agrees with the stance.”

UFT President Michael Mulgrew

In New York City teachers are represented by the United Federation of Teachers or UFT, and in my opinion, change toward a more “members first” approach is both timely and needed. I used to work for the UFT, and while I loved my job as a Special Representative, I knew that many members were not heard or helped, and this remains true today. That hurt. I left to do my own work to assist people crushed by malice, unfairness and/or discrimination.

I hope that the coming changes will lead to stronger unions who value members’ rights above all else and therefore earn the loyalty, rather than take it in order to support political campaigns and expensive hotel accommodations.

Let’s see what happens. I am hopeful that a new look at the rights of members to pay dues will bring union bigs to once again listen to the voices of those for whom unions were created, and not just pretend to hear what rank and file members want.

UFT may have to dramatically slash $182M budget

NY POST Reporter Carl Campanile wrote about how a US Supreme Court decision for Mark Janus would affect the UFT:

“The belt-tightening may have already begun. The event was held at UFT headquarters at 52 Broadway instead of the Hilton Westchester in Rye, NY, where the union typically holds its retreats…..

The UFT is a massive, far-flung enterprise with a $42 million payroll that includes more than 700 members paid to perform full-time or part-time union duties.

The payroll includes borough reps, district reps and 65 staffers each making more than $150,000. Mulgrew pulls in $283,000.

The UFT empire includes offices in all five boroughs and the lease of a building in Delray Beach, Fla., to serve thousands of retirees in the Sunshine State.

The budget also includes millions of dollars in spending to law firms and media and political consultants to advance the union’s collective-bargaining strategy and broader agenda. Millions more are spent on catered events, conventions and donations to allied groups, including the NAACP, New York Communities for Change and The Black Institute.”

Betsy Combier

Editor, ADVOCATZ.com

Arizona teachers protested in April in a statewide walkout, one of several this year. The walkout movement offered a glimmer of hope for teachers’ unions, which lost the right to collect agency fees.CreditMatt York/Associated Press

What the Janus Decision Means for Teacher Unions

By Dana Goldstein and Erica L. Green, New York Times, June 27, 2018

It has been months of whiplash for teachers unions. The nation’s highest court decided on Wednesday that they, and other public sector unions, can no longer collect agency fees, which are currently mandatory in 22 states.

The ruling came down after the unions racked up a series of victories early this year, taking part in teacher walkouts in six states and winning raises and new education dollars from conservative lawmakers.

Now, teachers unions could lose up to a third of their members and funding as a result of the decision, labor experts say, some of the same money that fueled the walkouts.

“Members and money are power in politics,” said Terry Moe, a Stanford political science professor who has written critically of the unions. “This will weaken the teachers unions nationwide as a political force.”

The walkout movement began in West Virginia, where agency fees are already outlawed, and was largely driven by rank-and-file teachers, not union leaders. While union members pay dues, agency fees cover the costs of representing nonmember teachers in contract negotiations and disputes with management.

The decision in the Supreme Court case, Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, “will affect us, because it’s going to hurt the national” unions that provided crucial support, said Jay O’Neal, a West Virginia teacher and a leader of the protests.

States with agency fees and public sector collective bargaining, he said, tend to have higher teacher salaries and school funding than right-to-work states like West Virginia and the others where teachers went on strike.

[Read more on the Supreme court decision and its impact on labor unions.]

Nonmembers can already opt out of paying for political lobbying. But because unions engage in politics even at the bargaining table, on issues such as how public dollars are spent on salaries and benefits, five of the court’s justices said such fees violate workers’ free-speech rights, by forcing them to give money to organizations whose views they may not support.

Given the court’s conservative tilt, the two national teachers unions have considered the ruling all but a foregone conclusion for several years. They plan to reduce budgets and cut back on activities like conferences.

Public sector unions have been under attack for years. Several states, including Iowa, Michigan and Wisconsin, have passed laws aimed at weakening them, and membership has declined, even in places where unions continue to represent teachers and other public sector workers in contract negotiations.

About 70 percent of the nation’s 3.8 million public school teachers belong to a union or professional association, according to a 2015-16 survey by the National Center for Education Statistics, down from 79 percent in the 1999-2000 school year.

Lily Eskelsen García, president of the National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers union, said that the Janus decision could mean a loss of up to 200,000 members: $28 million less in the organization’s $366 million budget.

The union is preparing a campaign to mitigate the fallout, in particular reaching out to younger teachers who do not have deep loyalties to organized labor.

“We know it will have an impact, and we know we will come back,” Ms. Eskelsen García said.

The National Education Association does not plan to curb its political activities, which are largely on behalf of Democrats and liberal groups. Among the union’s priorities is mobilizing teachers to vote in this year’s midterm elections, Ms. Eskelsen García said.

Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, said the Janus decision reversed a “fundamentally unjust” requirement that forced teachers to pay for the union’s political agenda.

“This restores teachers’ ability to say, ‘I will not support speech or political activity that I don’t agree with,’” he said.

For union allies stung by the court decision, the walkout movement offered a glimmer of hope. The protests occurred in states crippled by education funding cuts since the recession, and where unions are already weak and working without agency fees. Union affiliates in several of the states, including Arizona, North Carolina, Oklahoma and West Virginia, said they had signed up hundreds or even thousands of members since the movement began.

In Arizona, where the walkout prompted Republican lawmakers to give teachers a raise, the Arizona Education Association attracted 2,000 new members this year, compared with an average of 400 to 600 in previous years, the group’s president, Joe Thomas, said.

In many of the walkout states, the teachers who led the protests first gathered supporters on Facebook, sometimes with little help from union officials. But the state and national unions stepped in with organizing and lobbying muscle — and money — that sustained the movement as it grew. That support could wane if teachers in strong-union states like California or Illinois choose not to pay dues and fees.

Despite having worked together during the protests, some walkout leaders have little loyalty to unions. In Oklahoma, Alberto Morejon, a 25-year-old middle-school history teacher, started a Facebook group that pushed for the walkout. Many in the group were frustrated, he said, by union leaders whom they believed were not responsive to their concerns, and whom they felt were too quick to call off a nine-day labor action in Oklahoma in April.

“Teachers starting off, the salary is so low,” Mr. Morejon said. Foregoing union fees means “one less thing you have to pay for. A lot of younger teachers I know, they’re not joining because they need to save every dollar they can.”

A recent survey of 1,000 traditional and charter school teachers across the country, commissioned by the advocacy group, Educators for Excellence, gave a preview of the challenges facing unions. While most of those surveyed said that working conditions would be worse without union representation, six out of 10 nonunion members currently paying agency fees said they would likely opt out after the ruling.

Anticipating the decision, some leaders have sought countermeasures. In April, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo of New York, where public sector unions remain powerful, signed a law freeing the unions from the legal requirement to represent workers who have not paid dues in disputes with management. Labor experts say this will likely encourage teachers to maintain their union membership. Other liberal states may follow.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation for Teachers, the other national teacher’s union, remained optimistic: Of 800,000 members in 18 states affected by the Janus decision, the group said it had secured more than 500,000 “recommitments” to retain membership since January. About 90 percent of the A.F.T.’s 1.8 million members are school educators.

The Trump administration and its conservative allies that funded Janushave made it easier to make the case for union membership, Ms. Weingarten said.

“These folks that have huge power over their lives have tried to cut school budgets, tried to hurt their health care, cut retirement benefits, privatize hospitals and schools, are now having the chutzpah to say, ‘Give up your union to get a quick raise,’” she said. “People are getting it big time, and are basically trying to stick with the union.”

Patrick Semmens, a spokesman for the National Right to Work Legal Defense and Education Foundation, whose lawyer argued the Janus case, said the decision would not prevent union leaders from bargaining on behalf of its members. But it would expose whether they were in tune with their members’ best interests.

“It’ll mean that teachers can now hold union officials accountable,” Mr. Semmens said. “It allows them to say, ‘If you want my money, you have to earn it now.”’

JANUS AND TEACHER SALARIES: This week, the Supreme Court’s ruling on the closely-watched Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees case is likely to leave public educators feeling uneasy.

The ruling, a 5-4 split in favor of the plaintiff, Mark Janus, a child support employee at the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services, is expected to have a national impact on the wallets, power, and influence of unions. At a high-level, the case concerns whether public-sector employees who indirectly benefit from union representation must still pay union fees, even if they are not involved (or have no interest) in the union. (For more details, see this Vox explainer)

Today’s ruling will legally make all states “Right to Work,” meaning employees who choose to opt out of unions can no longer be forced to pay dues.

Traditionally, union leaders have justified forcing non-members to pay dues by noting how such employees indirectly benefit from union bargaining. For example, in New York City where union leader Michael Mulgrew recently negotiated the first paid parental leave agreement for teachers, all teachers — union members or not — have the right to take advantage of the new rule. In states where teachers have gone on strike over low teacher salaries, some teachers’ unions have been able to successfully negotiate higher pay.

It is unclear how the Janus ruling will make things easier or more difficult for unions in the future. But several organizations on the right and left are already weighing in, noting what this might mean for teacher unions in the future.

Read the court’s decision here.

Supreme Court’s Janus v AFSCME ruling will force unions to be more accountable: Teacher

Aaron Anthony Benner, Opinion contributor, Published 10:14 a.m. ET June 27, 2018

The decision affects 5 million workers. Time

Unions can be great for workers. But supporting workers’ rights isn’t political, and it doesn’t make you anti-union.

As a teacher in Minnesota, I didn’t have a choice about whether or not to pay the union that was supposed to represent me, and when my union ultimately failed to stand by my side during a dispute with my district, I had no choice but to continue paying it.

Fortunately for teachers and other public employees across the country, no government worker will be forced to pay a union just so they can keep their job moving forward. The Supreme Court has ruled in Janus v. AFSCME that requiring someone to pay a union violates the First Amendment’s protections of free speech and association.

It means that, if another teacher or public employee is let down by his or her union, that person doesn’t have to continue paying dues or fees if that’s not in his or her best interest. Or, if that person chooses not to belong to a union for any other reason, he or she could continue working anyway. In addition to being fair to workers who deserve the freedom to choose whether or not to pay a union, I believe this ruling will lead to unions that are more responsive and attentive to their members.

I come from a union family and was brought up, as many Americans are, believing that unions exist to protect their members. My father was a police officer; my mother was a factory worker. As a public school teacher, I belonged to a union for 15 years and always believed that the union would be there to fight for me if I ever had a problem with my employer.

When I finally needed my union — the Saint Paul Federation of Teachers — not only did it fail to defend me, it actively worked against me with my employer. And all the while, I had to keep paying.

It started in 2014, when Saint Paul Public Schools rolled out a new policy with the hope of lowering the suspensions of African American students. As an African American myself, I took issue with the idea that some behavior problems would be classified as cultural traits, and thereby excused, under this policy. The intent was good, but in practice, it was fraud, and I couldn’t sit by and watch my students be harmed.

After challenging the policy at a school board meeting, I was faced with multiple frivolous investigations, which I’m now challenging in court. My spotless teaching record was marred, and my union was nowhere to be found.

I eventually began speaking to the media about the destructive racial equity policy, bringing a spotlight to the district. Soon, I learned that my union — which I was still paying — was working with my employer to remove me. Ultimately, I chose to leave my teaching job in public schools, but I have continued educating students in the private sector as the ninth-grade dean of students and activities director at Cretin-Derham Hall High School.

In February, when the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Janus v. AFSCME — a case from Illinois that challenged the precedent that public employees can be forced to pay a union in order to work — I joined other teachers on the courthouse steps to support plaintiff Mark Janus. I shared the story I’ve just outlined and how my experience changed my mind about unions and freedom.

I was surrounded by people rallying in favor of giving people a choice and voice when it comes to unionism, but there were also union protesters who tried to shout me down and block out the signs supporting Mark Janus. I and other speakers were dismissed as being anti-union and Republican. I’m neither. Supporting workers’ rights isn’t political, and it doesn’t make you anti-union.

I like unions and always have. I voluntarily belonged to one for many years, and my parents were both represented by unions that I believe served them well.

But I realized that not all unions work for their members like they should, and in those cases, members should have the ability to leave — and take their hard-earned money with them.

Fortunately, for public employees across the country, the Court has now ruled they have that right.

Aaron Anthony Benner has been a Minnesota educator for 21 years. He worked as a teacher in Saint Paul Public Schools and was a member of the Saint Paul Federation of Teachers for 15 years. He is now the ninth-grade dean of students and activities director at Cretin-Derham Hall High School.